This article was originally featured in the May-June 2019 issue of Dancetrain magazine.

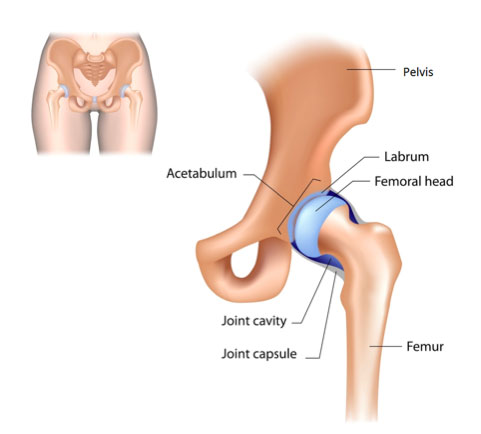

The hip joint is created where the thigh bone (femur) meets the pelvis.

Figure 1: Hip Joint Bony Anatomy

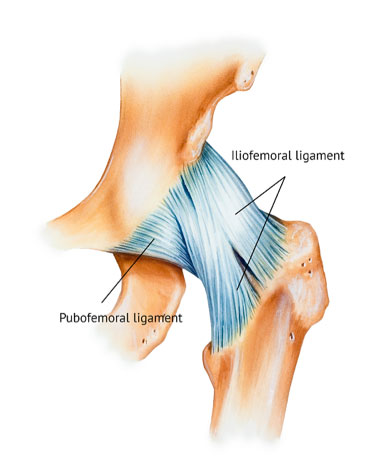

This Hip Joint is a ball and socket joint, with the ‘ball’ being the femoral head, and the ‘socket’ being the acetabulum which sits within the pelvis. This acetabulum is shaped like a half sphere, and is made deeper by a rim of cartilage around its edge. This rim of cartilage contributes to the stability of the hip joint, and is called the labrum. Further increasing hip joint stability is a strong fibrous capsule that surrounds the hip joint, and is reinforced by 3 strong ligaments – imagine ligaments a bit like short ropes that stretch across a joint and become taut with certain movements (figure 2), limiting hip range. While this might sound annoying (particularly if they’re limiting turnout), remember – stability in the hip is critical. Afterall we rely on our hip stability to hold us upright when we walk, run, and pirouette.

Figure 2: Hip Joint showing 2 of the 3 stabilising ligaments

So there you have it: the very basic structure of the hip joint. But here’s the thing. No 2 hips are created equal. Although each of the bones that make up the hip have similar characteristics, each of us will have individual variations in our bony make up. For example, some dancers have acetabulum (hip sockets) that face more forward (limiting turnout potential), and others have sockets that face more back (creating a more naturally turned out hip). Some acetabulum are naturally quite deep (possibly limiting motion of the hip into développé 2nd for example), and others are quite shallow (allowing lots of hip movement, but less natural hip stability). And there are others.

Most of these anatomical variations owe themselves to genetics (thanks mum and dad!), and can’t be changed no matter how much we stretch or may wish them otherwise. It is important is that dancers understand their own bony limitations before they try to force their hips beyond these limits. Knowing what can be changed and what can’t, helps a dancer to focus their efforts in the right areas, and can avoid unnecessary injury.

It is important is that dancers understand their own bony limitations before they try to force their hips beyond these limits.

So we’ve talked about bony anatomy and stability, but obviously our hips (particularly dancer’s hips) also need mobility. For this we need to talk about our muscles, which are responsible for moving our hips in all directions.

Muscles of the Hip

We can’t describe all of the hip muscles in this article, but there are a few that dancers should be aware of, and will almost always benefit from strengthening.

1. Iliopsoas

This is the prime hip flexor muscle. In other words; the muscle that is primarily responsible for lifting the hip into développé devant. Weakness in this muscle not only decreases our ability to lift our legs high, it can also lead to compensation in other muscles which can have the effect of restricting our hip motion by preventing them from moving properly within the hip socket. Often, this can lead to pain and injury.

Figure 3: Iliopsoas

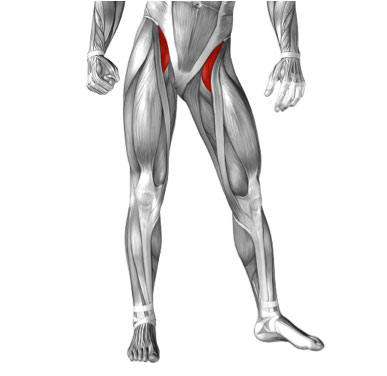

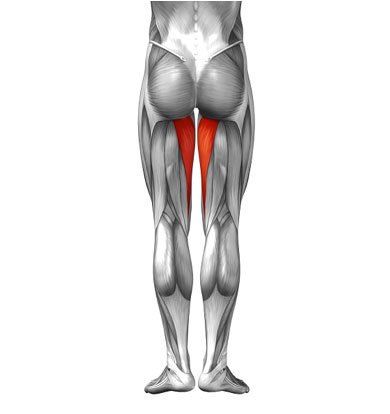

2. Adductor Magnus

A big muscle that runs down our inner thigh and helps to stabilise the hip in the socket. It needs to be strong in dancers to enable the femoral head to glide downwards as the leg lifts upwards into développé 2nd. In doing so, it assists in preventing pinching of the hip joint.

Figure 4: Adductor Magnus

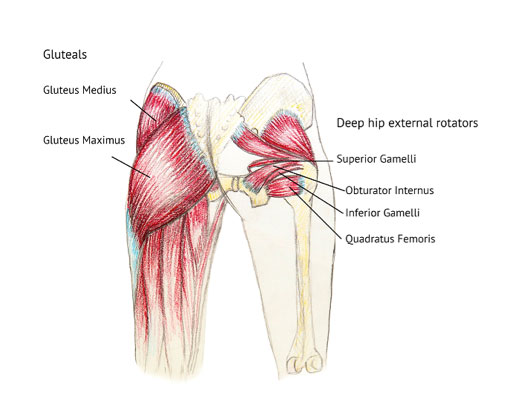

3. Deep External Rotators

These are our primary turnout muscles and are located deep in our buttocks. There are 6 of these muscles in total, and they are different to our gluteal muscles which are the superficial muscles we can see easily. If we don’t use our deep external rotators well, we won’t be able to turnout as easily. Often this leads to compensations including gripping with our upper gluteals, or tucking our pelvis too far under. Both of these strategies are unhelpful for dancers and can cause injury over time.

Figure 5: Deep External Rotators

Next issue we will look at common causes of hip injuries in dancers, and most importantly give you some tips on how to prevent them.

As always, keep dancing safely.